Oryang, Part 4 (Conclusion)

Much have been written about the loves of Rizal. There were at least 9, maybe 10 of them–an international cast stretching all the way from London to Japan: Segunda Katigbak, Leonor Valenzuela, Leonor Rivera, Consuelo Ortiga, O-Sei San, Gertrude Beckett, Nelly Boustead, Suzanne Jacoby (or Thill? or both?), and Josephine Bracken. Ambeth Ocampo adds up the body count to 13, with Rizal “serious enough to propose marriage to three of [them] in his short life: Leonor Rivera, Josephine Bracken and Nellie Boustead”, adding “[it] was the last, in my opinion, who was the prettiest of them all” (Loves of Rizal, Inq7.net). The prospect that this child-prodigy of Teodora Alonso was also (my, my!) a regular jackrabbit with a lusty lady waiting in every port of call is enough to spice up stodgy history lessons in Catholic prep schools.

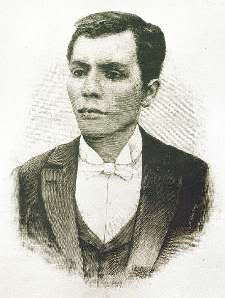

Leonor Rivera, Rizal’s model for Maria Clara, may have been the closest to being the love of his life. Their 11-year romance in letters kept him from falling in love with other women he met during his travels, even if it did not preclude him from flirting with them. Their tale of unrequited love could rival that in Love in a Time of Cholera, where Fermina Daza, waking up to the frivolity of their epistolary romance, promptly rejects the passionate advances of Florentino Ariza and marries the more sensible Dr. Juvenal Urbino. “Leonor’s mother [on the other hand] disapproved of her daughter’s relationship with Rizal, who was then a known filibustero. She hid from Leonor all letters sent to her sweetheart. Leonor believing that Rizal had already forgotten her, sadly consented to marry the Englishman Henry Kipping, her mother’s choice” (from JoseRizal.Ph). Stewing up the melodrama are anecdotal accounts of Leonor Rivera burning Rizal’s letters the day before her wedding, gathering all the ashes and tenderly sewing them into the hem of her wedding gown. “Thus, as she walked down the aisle to marry a man we are told she did not love as much, she felt the pieces of a lost love crumble at her feet” (Love letters to Rizal, Inquirer.net).

|

Leonor Rivera (right) with mommy. Notice her dazed expression as mum clutches her cuello while holding a fan like a whip. Mata lang ang walang latay! Aray ko po! |

But even while Rizal reserved his true love for Leonor Rivera, like Florentino Ariza, he allowed, even encouraged, casual diversions during his travels. He had flings with other women. For how can we read Suzanne’s (Jacoby/Thill?) giddy and taunting letters otherwise:

…I hope your courts are open and I shall not have to wait a long time for your decision. Don’t delay too long writing us because I wear out the soles of my shoes running to the mailbox to see if there is a letter from you.

*****

There will never be any home in which you are so much loved as that in Brussels, so, you, little bad boy, hurry up and come back. Tell us a little about the kind of house in which you are lodged and how are the people there. (Love letters to Rizal, Inquirer.net)

This actually reminds me of a coy love letter, flower enclosed, to Leopold Bloom–posing as Henry Flower–from his amorous pen pal, Martha Clifford, in James Joyce’s Ulysses.

I got your last letter to me and thank you very much for it. I am sorry you did not like my last letter… I am awfully angry with you. I do wish I could punish you for that. I called you naughty boy because I do not like that other word. Please tell me what is the real meaning of that word. Are you not happy in your home you poor little naughty boy? I do wish I could do something for you. Please tell me what you think of poor me…

What do we make of 13 love affairs and three marriage proposals, two of which did not materialize? It’s certainly more love than a man can handle in a lifetime, but, then again, this is Rizal we are talking about–the über-über-Filipino might also be just as macho as he is matalino. Ambeth Ocampo in Rizal, Freud and the failure of psycho-history observes, however, “that the fact that Rizal had many women was probably an indication that he was incapable or perhaps had difficulty in maintaining a stable relationship with one woman… [he] would court a woman or show interest in her and when a relationship is formed and he is at that point of intimacy, Rizal would suddenly withdraw”.

Bloom tears up the letter, and at the end of that episode, as he takes his bath, Joyce invokes the flower image again, not to signify the awakening of amorous feelings, but the soporific surrender of a man, feeble and flaccid: “He foresaw his pale body reclined in it at full, naked, in a womb of warmth, oiled by scented melting soap, softly laved. He saw his trunk and limbs riprippled over and sustained, buoyed lightly upward, lemonyellow: his navel, bud of flesh: and saw the dark tangled curls of his bush floating, floating hair of the stream around the limp father of thousands, a languid floating flower”.

Was he just toying with poor Suzanne, or, was he really frigid, or worse, impotent, at least when it comes to the affairs of the heart? Or, perhaps, for Rizal, women were simply too intractable, like those elusive flowers of Heidelberg–fremde Blumen, strange flowers.

|

“kaya isipin ninyo mga kapatid kung katoiran o hindi ang kanilang ginagawa pag api sa amin…” |

Oryang in her Talambuhay prudently skips over the quarrel (sigalot) between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo that began with the elections in Tejeros, their persecution and humiliation at the hands of Aguinaldo’s men, that eventually led to Bonifacio’s death. She, however, cryptically refers to having written a letter to Emilio Jacinto, that to her knowledge is supposedly in the hands of Jose P. Santos, the same fellow who was requesting her to write her autobiography in 1929. Another blogger, notes how Oryang–“in almost guarded language”–carefully weighs in on the provenance of the documents in Santos’ possession. She attests to having written accounts to Emilio Jacinto, but stops short in stating for a fact that these are what Santos has in his keeping. She was making sure the record was set straight with regards to her own version of the events in Cavite.

Ambeth Ocampo quotes a letter to Emilio Jacinto (is it the same letter?) written close to the events of 1897, where Oryang related her first encounter with the executioners, as she desperately went looking for her husband and brother-in-law.

…kinabukasan ng tanghali nila inalis ang dalawang magkapatid, at ng bandang hapon na ay nagkaroon ng laban sa labas ng bayan na di malayo sa aking kinalalagyan. Saka lamang ako pinakawalan. Nang ako’y makawala at ako’y tumawid ng ibayo at aking hinahanap ay nasalubong ko ang nang hatid na dala ang papalimusan kong damit na siya kong ibinibihis pati kumot gamit sa katawan ng aking bayaw. Ng ako’y itanong kung saan naroon ang kanilang dala ang sagot sa akin ay naroon sa Bondok sa isang bahay ng tuti [puti?], itinanong ko kung bakit nila dala ang damit. Ang sagot ay ako na raw ang siyang biling magdala. (Gregoria de Jesus Nakpil, undated letter to Emilio Jacinto. Original manuscript in The Encarnacion Collection)

In Santos’ records (“Tenepe” Si Andres Bonifacio at ang Himagsikan. Typescript in UP Library. Manila: n.p. 1935), Oryang gives a more harrowing account of her search for the bodies, of how she was given the run-around by Aguinaldo’s men, and of how Lazaro Makapagal, as if to twist the knife in, continued to lie to her and mock her.

Nang ako ay pakawalan nila ay hinanap ko si Andres Bonifacio. Sa bahay na aking pinagiwanan ay wala na at naipapatay na nila at sa katunayan ay nasalubong ko sa paglabas ng sular na nagtatawanan pa si Lazaro Makapagal at Jose Zulueta at tatlong sundalo pa, at ang isa ay pinalapit sa akin at ipinabigay ang balutan ng damit at sapatos na suot ni Andres at sinabi sa akin na, Perdon na, Señora.

Ay! Mga kapatid! Minulan ko na ang hanap sa pinajeruan sa akin ay natagpuan ko pagdating doon ay itinuro ako sa kabilang Bondok na labis ang taas ang inakyat. Ng kami ay dumating ay wala. Lakad na naman kami. Ay! Mga kapatid! May dalawang linggo kong hinanap sa Bondok na walang tigil kami kundi gabi. Nang di ko makita at walang makapagsabi. Kami ay sumunod sa kanilang tropa at kahit ang aking pagtanungan sa kanila ay kung saan saan ako itinuturo magpahanggang ngayon. Kaya lamang ako natuluyang ng paglabas [sa Cavite] ay nang nakausap ko ang aking amain [Mariano Alvarez] na sinapi sa akin na tapat… kaya isipin ninyo mga kapatid kung katoiran o hindi ang kanilang ginagawa pag api sa amin…

One can almost palpably hear the outrage in her voice (Ay! Mga kapatid!), as she appealed to the Katipunan, or to some other higher authority, to be judge of the injustices they suffered in Cavite. With the trial, and possibly its records, rigged, with the sneaky way by which the execution was carried out, and with the absence of the bodies of the deceased, Oryang, as if to steady herself, concludes by putting on record the plain facts.

Ako ay hindi maaring malinlang ng sino pa man tungkol sa nangyayaring ito pagkat ako’y saksi sa lahat ng nangyari mula ng gawin ang halalan sa Teheros na siyang naging simula ng kaguluhan hanggang sa siya’y ipapatay o barilin na nangyari noong 10 ng Mayo ng taong 1897 na naganap sa ibayo ng barrio ng Marigundong, sakop ng Kabite, at kaya ko naman natatandaang 10 ng Mayo ay dahil sa kinabukasan ng aking pista ng kapanganakan siya binaril.

Ang mga hirap at sakit na dinanas ko sa kasawiang palad naming magasawa ay di ko na ibig magunita pagkat tunay na nadudurog ang aking puso. Pinabantayan ako na parang isang tunay na salarin o kriminal sa lahat ng kilos na ang dalawang tanod ay may dalang baril na nakalagay ang bayoneta.

…Ang nagsiganap ay si Lazaro Makapagal na katulong si Jose Zulueta na may kasamang ilang kawal na may dala ding mga baril. May kasama pa silang Cazadores na bihag na tila ang pangalan ay Juan Marinio na siyang nag-abot sa akin ng balutan at sapatos ni Andres na iniutos ni Makapagal.

With all the double-dealing she had endured to get to the bottom of things, she states in a very lucid and poised manner, why she cannot be deceived and why she can never forget. She speaks with the same indignation as future witnesses in the Nuremberg trials, or the torture victims of the Marcos regime. Yet, true to her husband’s dreams, in the end, Oryang yielded her rights of redress, as the moment for revolt against Spain was ripe, and unity among Filipinos what the times demanded.

Ang paghihiganti ng mga oras na yaon ay natiim ko sa kalooban dahil nasa gipit na kalagayan ang bayan at lahat ng lumapit sa akin na humihimok upang magsamasama kami sa paghihiganti ay sinasaway ko at pinagpapayuhan ng kapayapaan sa hangad kong magkaisa ang lahat at matamo natin ang kalayaan na siyang layon ng paghihimagsik laban sa mga kastila.

I originally set out to write a short account of the less celebrated love life of Andres Bonifacio for a Valentine’s Day blog entry. The literature about Bonifacio’s life was so thin compared to Rizal’s who seemed to have made sure he left a stockpile of memorabilia, all over the world, as if he had prescience of his heroic destiny. While there are endless anecdotes about Rizal’s courtly ways with women, I did not find any gushing love letters for Bonifacio. All we know is that he had a first wife who died of leprosy, and that he re-married with 18-year-old Gregoria de Jesus, in secret Katipunan rites. What an extraordinary woman Oryang turned out to be. Not bad for someone he was thought to have met in a town fiesta or a baile, and courted for about six months. By 21, she would be deeply entrenched in the flames of a revolution sweeping the country, that her husband sparked. She would also be a widow. Theirs was a love that endured the worst, but survives through her witness and her voice.