Los Caprichos: Goya’s Comedy of Horrors

by Kiko Matsing

I found a used copy of Francisco Goya’s Los Caprichos at the Smathers Library bookstore. This Dover Fine Art Books edition reproduces all 80 aquatint prints in black and white, with 6 additional prints of preliminary studies and unique proofs. Goya produced Los Caprichos after coming out of a mysterious and debilitating illness in his fifites that left him “a changed man: bitter at times, secretive, far less exuberant” (p. 2). It proved to be a turning point in his artistic development.

To be sure he was one of the court painters of King Carlos IV, but had he died before the drawings and prints for Los Caprichos were made, he would today be rated as an attractive painter of the pre-Revolutionary era and, in graphics, as mainly a reproductive etcher–not the major artist and the father of modern art which he had started to become. (p. 1)

Caprichos literally means ‘fancy’ or ‘whimsy’, but there is certainly nothing fanciful or whimsical (in the ordinary sense of lightness or playfulness) in Goya’s Los Caprichos. It is also not properly horror, despite the attendance of witches, devils, and hobgoblins. It is rather said to be a satirical attack on 18th century Spanish society, specifically “the Spanish Inquisition, the corruption of the church and the nobility, witchcraft, child rearing, avarice, and the frivolity of young women” (Indepth Arts News, Portland Museum of Art). I do not know anything about 18th century Spanish society, but I can still catch echoes of Goya’s contemptuous laughter through his unsettling images. The dead-pan commentary of the Prado manuscript certainly helps. That these graphic prints still manage to convey the artist’s dour humours two-hundred ten years later attests to both his gothic and comic genius.

4. Nanny’s boy. Negligence, tolerance and spoiling make children capricious, naughty, vain, greedy, lazy, insufferable. They grow up and yet remain childish. Thus is nanny’s little boy.

What’s monstrous about this picture is ostensibly the tacking of a grown man’s head onto a little girl’s body. To me, even more repugnant than his thick eyebrows or mustachioed lips, are his stubby hands, fingers stuck in the mouth, and those heavy boots beneath the daintily embroidered skirt.

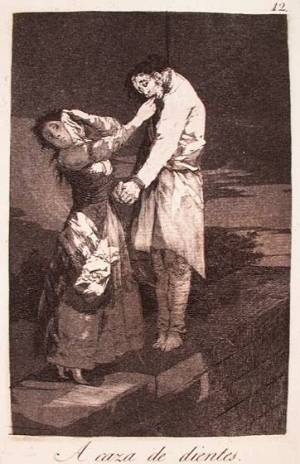

12. Out hunting for teeth. The teeth of a hanged man are very efficatious for sorceries; without this ingredient there is not much you can do. What a pity the common people should believe such nonsense.

The hanged man is obviously bound and dead. So why does the woman (or witch?) make the affected gesture of covering her face? She pulls at his teeth in the same delicate manner she would perhaps sew a dress. She tiptoes to reach for it, teetering it seems on a high wall, lunging forward, while at the same time, pulling back.

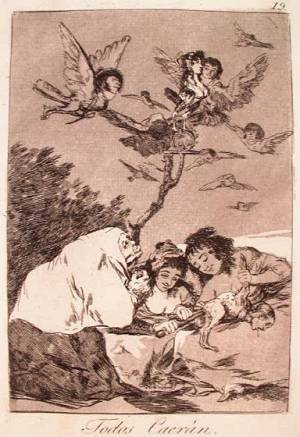

19. All will fall. And those who are about to fall will not take warning from the example of those who have fallen! But nothing can be done about it: all will fall.

This could have been a charming rustic scene of scullery maids preparing a chicken–the women’s faces certainly convey this–except that they are casually violating the poor thing. (Why?!) It’s Willem Joseph Laquy meets Hiernonymus Bosch. The commentary reminds us, with a keen tragic sense, of the certainty of ruin.

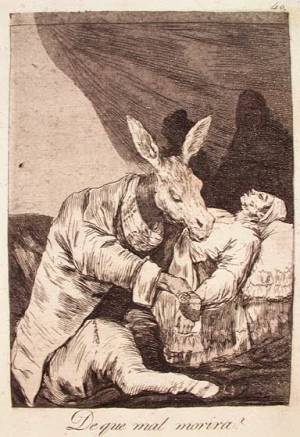

40. Of what ill will he die? The doctor is excellent, pensive, considerate, calm, serious. What more can one ask for?

Having suffered from protracted illness doctors could not diagnose, Goya must have detested the lot, portraying them as phony experts who professed false authority over diseases, while man’s true reality is sickness unto death.

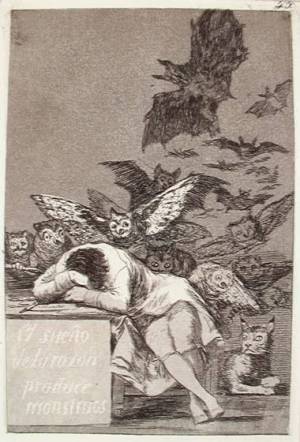

43. The sleep of reason produces monsters. Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of her wonders.

The most well known print from Los Caprichos. Rousseau and the Enlightenment informed its condemnation of stupidity and superstition. The cat, though, looks like a knowing sphinx.

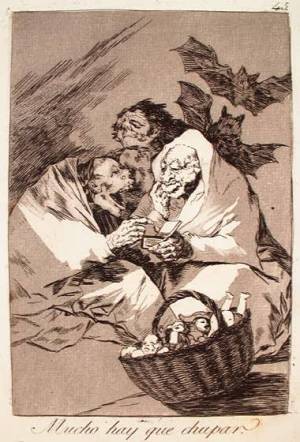

45. There is plenty to suck. Those who reach eighty suck little children; those under eighteen suck grown-ups. It seems that man is born and lives to have the substance sucked out of him.

Again, that capitulation to fate. Even children are not exempt; here, they are bought and sold like common victuals. Goya uses the desecration of innocents–a staple in witchcraft (see for example Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan, 1922)–to convey our tragic condition.

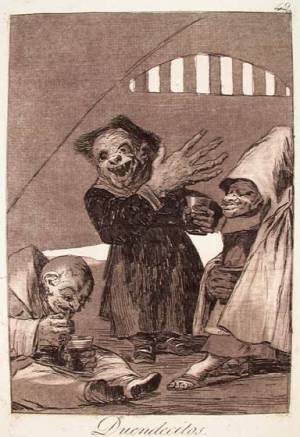

49. Hobgoblins. Now this is another kind of people. Happy, playful, obliging; a little greedy, fond of playing practical jokes; but they are very good-natured little men.

Those over-sized hands with knobby joints make their feet look more grotesquely small. How can they be described as both “a little greedy” and “very good-natured little men”? I think the descriptive ‘little’ is the operative word.

51. They spruce themselves up. This business of having long nails is so pernicious that it is forbidden even in Witchcraft.

A demon enjoying his pedicure. The clumsy shears on the hooked nail counterpoints with the pedicurist’s meticulous attention.

55. Until death. She is quite right to make herself look pretty. It is her seventy-fifth birthday, and her little girl friends are coming to see her.

This reminds me of some of Manila’s aging, pasty-faced socialites, who still insist on dressing up like debutantes.

61. They have flown. The group of witches which serves as pedestal for this fashionable lady is put there for ornament rather than for use. There are heads so full of inflammable gas that they need neither baloons nor witches to make them fly.

For some ‘fashionable’ ladies who appear in Manila’s society pages, it is not enough to have a mammoth butterfly pinned on their heads.

66. There it goes. There goes a witch, riding on the little crippled devil. This poor devil, of whom everyone makes fun, is not without its uses sometimes.

Except for the commentary, there is really no indication that the figure in the foreground is a devil–no horns, serpent’s tongue, cloven feet. The bat’s wings seem more of a cloak or a shadow. The occult figures are composed like a Tarot card. Is it a coincidence that this is the 66th print?

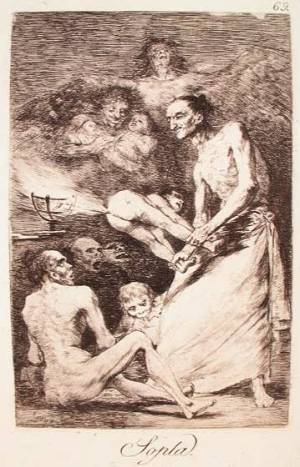

69. Blow. No doubt there was a great catch of children the previous night. The banquet which they are preparing will be a rich one: “Bon appetit”.

What is wicked here is not that children are about to be served in a witches’ banquet, but that their flatulence is used like gas from bellows to fan the flames.

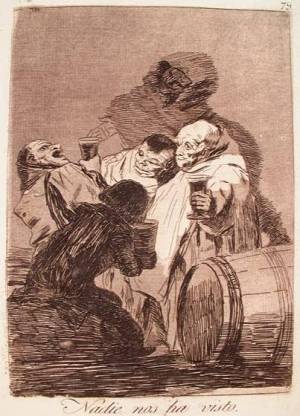

79. No one has seen us. And what does it matter if the goblins go down to the cellar and have four swigs, if they have been working all night and have left the scullery like gleaming gold.

The glare of light make their faces look like macabre masks. These goblins look garbed like monks, drunk on altar wine.

Related Links:

ha, funny pics man

LikeLike

I think that Blow is about the sexual abuse of a child, not necessarily that they are just eating them. Look at the man in the back. What do you think is in his mouth?

LikeLike