Two Early Brocka Films: Insiang and Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang

I found two early Lino Brocka films on Netflix (the online DVD rental service): Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang (1974) and Insiang (1976). Both belong to the short list of Brocka’s finest works from the 1970’s to the early 1980’s.

Tinimbang Ka was Brocka’s breakout film, starring Lolita Rodriguez, Christopher de Leon, Eddie Garcia, and scriptwriter Mario O’Hara in a pivotal role. In many ways, the script and directing here is still unrefined, and the film often lapses into unnecessary melodrama, but it nonetheless indicates the best of things to come: Maynila sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag (1975), Insiang, Jaguar (1979), Bona (1980), and Bayan Ko: Kapit sa Patalim (1985)–Brocka’s more committed social realist work. Known for their preferential sympathy for the poor, Brocka’s films can nonetheless be grim and pessimistic about their prospect in life. The characters remain trapped in cramped spaces, unable to escape the vicious cycle of poverty; their defeat is assured from the start. His films, however, are not as humorless as commonly fussed about. Some of the best scenes in Brocka’s films involve droll, almost documentary rendering of Filipino life, probably best appreciated by insiders. The funeral scene where the townsfolk prop the casket up and take turns taking pictures with the corpse is perhaps one of my favorites in Tinimbang Ka.

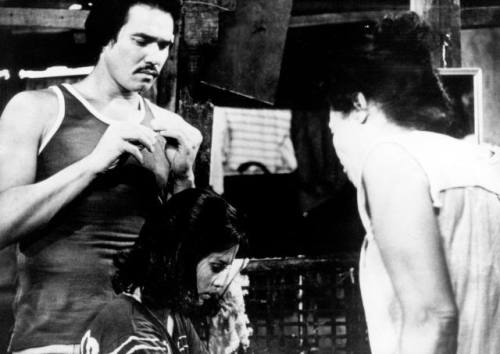

Insiang, starring Hilda Koronel, Mona Lisa, and Ruel Vernal, has the reputation of the first Filipino film to be screened at the Cannes Film Festival (1978). It is without reservation my favorite Brocka film. Shot in the slums of Tondo through neorealist lenses, its domestic melodrama at the same time aspires to Greek tragedy. It is Brocka’s tightest, most well composed film; the character’s fates play out inevitably from the opening slaughterhouse scene to the catastrophic last act. As usual, Brocka brings levity to the nastiness of poverty with cinema verité details, as when Tonya very publicly throws out a clan of in-laws living in her shanty. She demands the clothes she had given the children to be handed back; their mother, outraged, strips off the garments from the bewildered kids right there on the streets. This, for me, is the punctum of the film, as Barthes would say. There is another: at the end, when Insiang visits Tonya in prison, she confesses to her mother that she deliberately provoked her jealousy in order to get back at Dado; Insiang rushes to embrace her, and there, for a split second, Tonya’s expression yields to motherly tenderness, before quickly turning, once again, into that of the jealous rival.

Brocka’s films are are always marked by strong acting, not just from the stars, but also from the rest of the cast; there is a feeling of an ensemble effort, which is not unexpected, since Brocka brings with him the crew of the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) Kalinangan Ensemble. I saw Insiang for the first time on the big screen when a print restored by the French government was played in a Makati theater. Mona Lisa, silver-haired, graced the screening.

Insiang in review:

- From Film Society of Lincoln Center, a long-winded academic review from José B. Capino: “This [slaughterhouse] sequence seemingly foreshadows the fate of Brocka’s waifish heroine… Too vulgar to qualify as allegory, this analogy aspires instead to exhaust the signifying powers of hyperbole… This calculated mimetic failure can be found in Brocka’s best work…”

- From Slant Magazine, a smart review by Nick Schager: “Brocka’s portrait of familial treachery and societal abandonment… channels its Sirk/Fassbinder melodrama through the filter of neorealism, its story’s heightened emotions kept at a simmer by an aesthetic at once verité-blunt and yet shrewdly, meticulously composed.”

- From Internet Movie Database, a gushing user comment by Noel Vera: “Insiang is arguably Brocka’s masterpiece–it’s his most intense work.”

- From Reverse Shot, a perplexed review by Michael Joshua Rowin that is more telling of the reviewer’s own lack of finesse: “Insiang is fueled with missionary morality, a sense that the world’s wickedness is a pure state in need of nothing less than divine clean-up.”

[This review is also posted at the Internet Movie Database.]