The Idea of “Elvish”, Part 2

2. Elves and Enchantment

(link to Part 1)

I said earlier that the Elves seem to embody what is fantastic and magical about Middle-earth, but what exactly is the nature of this Elvish magic?

By the end of the Third Age, the time of the Elves was passing, giving way to the dominance of Men. They were abandoning Middle-earth and going into the West over the Great Sea. Their realms were preserved in small pockets like Rivendell, Lothlórien, The Grey Havens (Mithlond), and The Woodland Realm. One feels in their passing that Middle-earth would be left a less magical place for it seems that Tolkien’s notion of “elvish” is what we really consider as “magical” in LOTR.

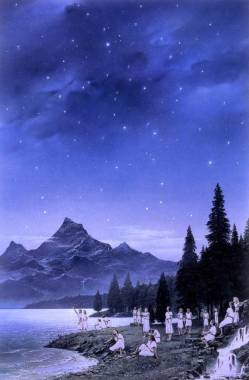

Awakening (Artwork by Ted Nasmith)

In Tolkien, the races appear (“awaken”) into the world pre-formed, and the circumstances of their “awakening” confer a certain character to their race. The Elves were the first-born who became conscious in a Middle-earth without a Sun–only stars. This imprinted a certain luminous quality to their being–not the glaring brilliance of sunlight–but the shimmering luster of twilight. Thus, they are often referred to as the “Fair Folk”.

In the very hour that Varda, the Lady of the Heavens, rekindled the bright Stars above Middle-earth, the Children of Eru [9] awoke by the Mere of Cuiviénen, the “water of awakening”. These people were the Quendi, who are called Elves, and when they came into being, the first thing they perceived was the light of New Stars. So it is that of all things, Elves love starlight best and worshipped Varda, whom they know as Elentari, Queen of the Stars, over all Valar. And further, when the new light entered the eyes of Elves, in that awakening moment, it was held there, so that ever after it shone from those eyes. Thus Eru, the One, whom the Earthborn know as Ilúvatar, created the fairest race that ever was made and the wisest.

(p.144, Tolkien Illustrated Encyclopedia)

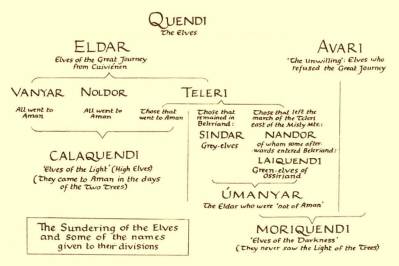

Sundering of the Elves (The Silmarillion)

Of the Elves, there were three principal races: the Vanyar—the fair elves, most valiant, wisest, and loved poetry & song; the Noldor—deep elves, loved knowledge above all, were craftsmen, wrought the Silmarilli and the Palantiri; and, finally, the Teleri (sea elves) from whom came Nandor (“those who turn back”), Sindar (grey elves, who remained in Beleriand), and Lindar (sea elves, loveliest of singers). Some of the Nandor Elves became Silvan (woodland elves, e.g. of Greenwood & Lothlórien [10]).

Black Riders drowned by the river Bruinen under Elrond’s spell.

(Artwork by Julia Alekseeva at CGSociety)

Now, let us go back to our question: What is magical about Elves? We don’t really see Elves performing spells or magic tricks like the students at Hogwarts, but we do understand that they have some power over Nature. In the book, Elrond [11] commanded the river to deluge the Ring Wraiths, because “[the] river of this valley is under his power, and it will rise in anger when he has great need to bar the Ford.” (p.236, FOTR) Legolas was quick to tame the “restive and fiery” horse Arod, given him by Eomer, “with [but] a spoken word [for] such was the elvish way with all good beasts”. (p. 42, TT) It seems that this is not exactly power over Nature, but rather a profound connection that allows Elves to work in accord with Nature, which gives the appearance that they are not subject to the elements. When the Fellowship, for example, encountered a violent snowstorm at Caradhras,

[Legolas] sprang forth nimbly, and then Frodo noticed as if for the first time, though he had long known it, that the Elf had no boots, but wore only light shoes, as he always did, and his feet made little imprint in the snow… Then swift as a runner over firm sand he shot away, and quickly overtaking the toiling men, with a wave of his hand he passed them, and sped into the distance, and vanished round the rocky turn.

(p. 305, 306, FOTR)

Although Sam calls them the “Fair Folk”, Tolkien’s Elves are not like the diminutive fairies with sparkling wands and butterfly wings. Rather they are tall, lean, majestic creatures–almost like angels–and they can look terrible when they reveal themselves in full glory. Glorfindel [12] became a “shining figure of white light” as he charged at the Nazgûl at the Ford of Rivendell. Galadriel became similarly transfigured before Frodo in Lothlórien:

She lifted up her hand and from the ring that she wore there issued a great light that illumined her alone and left all else dark. She stood before Frodo seeming now tall beyond measurement, and beautiful beyond enduring, terrible and worshipful.

(p. 381, FOTR)

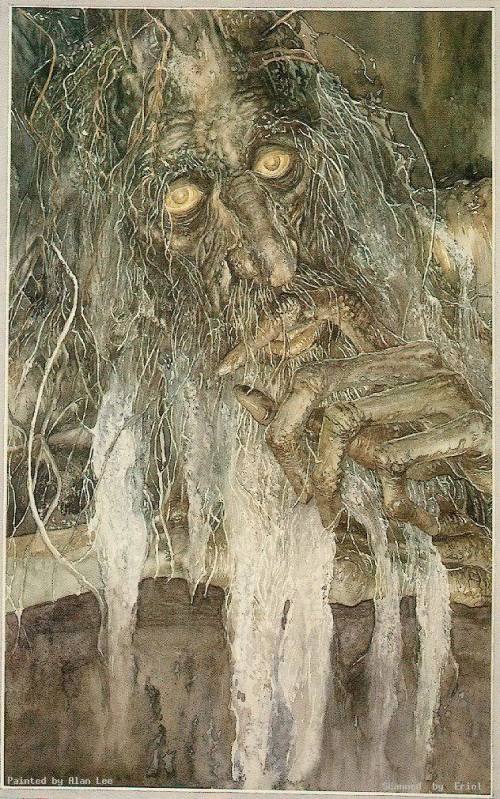

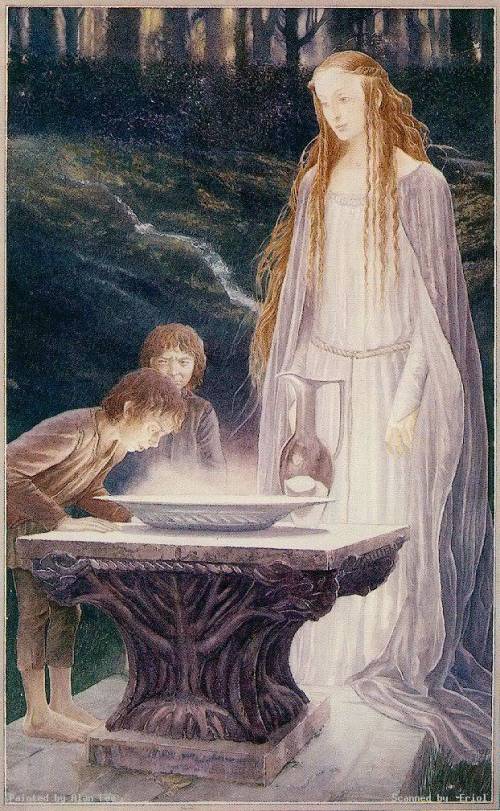

It’s a rare treat to see Elves in this sublime state in LOTR. What we normally encounter as magical are in the ordinary things that they do extraordinarily. Elves love music, song, and poetry. Their language, as Tolkien would say, is “phonaesthetic” or beautiful-sounding, and lend itself to song and poetry. They love arts and crafts, and making beautiful things that to us seem magical: The Mirror of Galadriel, Sam’s rope, the concealing cloaks, lembas, miruvor, mithril mail, the Palantiri, etc.

Tolkien, in fact, refuses to call these effects magic, but rather enchantment, and differentiates the two:

Enchantment produces a Secondary World into which both designer and spectator can enter, to the satisfaction of their senses while they are inside; but in its purity it is artistic in desire and purpose. Magic produces, or pretends to produce, an alteration in the Primary World. It does not matter by whom it is practiced, fay or mortal, it remains distinct from the other two; it is not an art but a technique; its desire is power in this world, domination of things and wills.

(p. 73, “On Fairy-Stories”, The Tolkien Reader)

Enchantment, like true art, cannot come from the exterior, but must be part of one’s being. These elvish objects have enchanting effects because they come from the Elves who are themselves enchanted. It is who they are; it is their being. As Fr. Roque Ferriols, my Jesuit philosophy professor, would say: Iyan ang pagmemeron nila.

Elvish articles (clockwise from top-left): hithlain rope,

lembas bread, Phial of Galadriel, mithril mail, Sting

“Are these magic cloaks?” Asked Pippin, looking at them with wonder.

“I do not know what you mean by that,” answered the leader of the Elves. “They are fair garments, and the web is good, for it was made in this land. They are elvish robes certainly, if that is what you mean. Leaf and branch, water and stone: they have the hue and beauty of all these things under the twilight of Lórien that we love; for we put the thought of all that we love into all that we make…” [13]

(p. 386, FOTR)

And what is the nature of this enchantment? Tolkien wrote:

I suppose that the Quendi are in fact in these histories very little akin to the Elves and Fairies of Europe; and if I were pressed to rationalize, I should say that they represent greater beauty and longer life, and nobility… The Elves represent, as it were, the artistic, aesthetic, and purely scientific aspects of the Humane raised to a higher level than is actually seen in Men

(p. 176, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien)

In other words, enchantment is an amplification of what is ideal in men. It is taking men’s best qualities and raising these to their highest potential. This, however, is double-edged: their elevated state also portend their essentially tragic nature for they also experience loss more acutely than mere mortals.

Ilúvatar declared that Elves would have and make more beauty than any earthly creatures and they would possess the greatest happiness and deepest sorrow. They would be immortal and ageless, so they might live as long as the Earth lived. They would never know sickness and pestilence, but their bodies would be like the Earth in substance and could be destroyed. They could be slain with fire or steel in war, be murdered, and even die of grief.

(p.144, Tolkien Illustrated Encyclopedia)

Elves thus represent a magnification of what is best and transcendent in man–in us! The meaning of their name (Quendi) gives us the key: “those that speak with voices for as yet they had met no other living things that spoke or sang”. (p.48, The Silmarillion) For Tolkien, linguist and writer, this is what’s especially transcendent in man: our capacity for language that gives shape to our consciousness and imagination. Language is also what makes Nature transcendent in LOTR, and in fantasy stories in general.

Fantasy is made out of the Primary World, but a good craftsman loves his material, and has a knowledge and feeling for clay, stone and wood which only the art of making can give. By the forging of Gram cold iron was revealed, by the making of Pegasus horses were ennobled; in the Trees of the Sun and Moon root and stock, flower and fruit are manifested in glory… It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of words, and the wonder of the things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine.

(p. 78, “On Fairy-Stories”, The Tolkien Reader, emphasis added)

In LOTR, Nature seems to be alive, in the sense of being imbued with this consciousness–it is pervaded by language through and through–from the Old Forest (Old Man Willow), to the eagle Gwaihir, to the horses of Rohan (Shadowfax, Hasufel, Arod), to the birds of Saruman, to the ill-willed Caradhras, and even Sam’s pony Bill. The Elves taught the Onodrim (Ents or tree-herders) the art of speech, and since then became one of the most loquacious of speakers in Middle-earth. In fantasy, language makes Nature once again strange to us, and rekindles in us our sense of wonder for things.

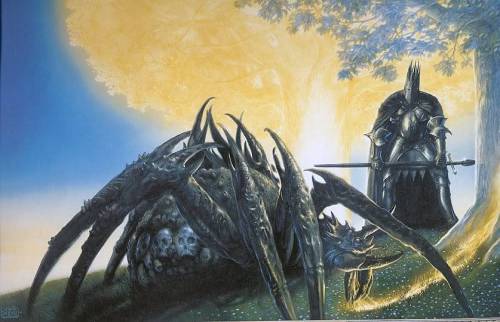

Sam defeats Shelob with Sting and the Phial of Galadriel.

(Artwork by John Howe)

Sam realized the power of this enchantment–of the Elves’ music and light–during his confrontation with the spider Shelob–not just to overpower evil, nor to command Nature–but also to inspire in him courage.

‘Galadriel!’ he said faintly and then he heard voices far off but clear: the crying of the Elves as they walked under the stars in the beloved shadows of the Shire, and the music of the Elves as it came through his sleep in the Hall of Fire in the house of Elrond.

Gilthoniel A Elbereth!

And then his tongue was loosed and his voice cried in a language which he did not know:

A Elbereth Gilthoniel

o menel palan-diriel,

le nallon si di’nguruthos!

A tiro nin, Fanuilos! [14]And with that he staggered to his feet and was Samwise the hobbit, Hamfast’s son, again.

(p. 338, 339, TT)

Sam then routed Shelob with the light from the Phial of Galadriel. Here the words and objects have the potency, not exactly of a magic spell (a technique for domination), but of that which emanates from the very nature of the Elves (light, poetry, and music) that contradicts the nature of Shelob (darkness, hunger, and malice) [15]. We are convinced of its power because we are convinced of the reality of the Elves in this “Secondary World”, and we are convinced of the latter because this had been worked out by Tolkien in language, in mythology, and in history.

3. Elegy

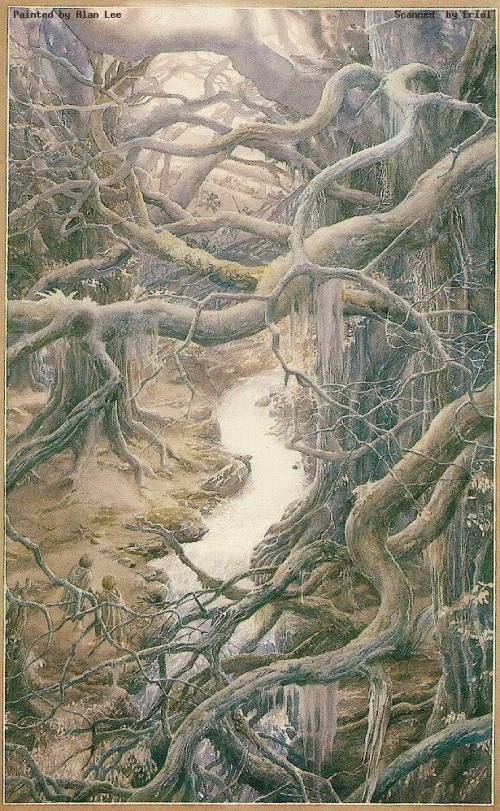

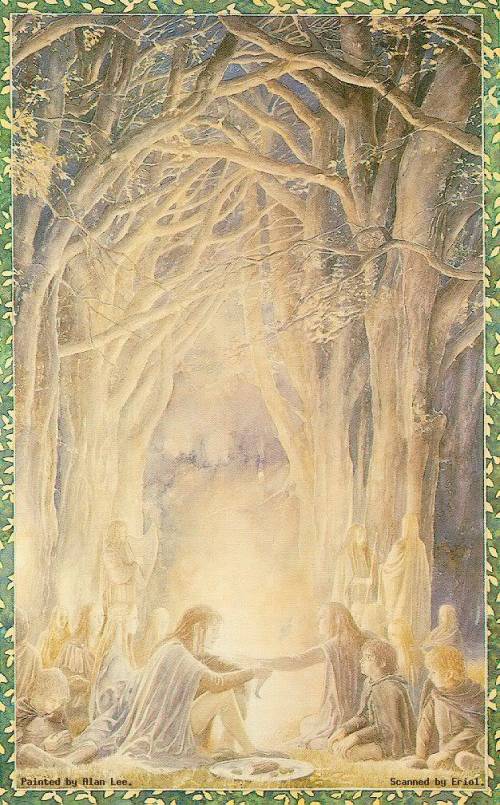

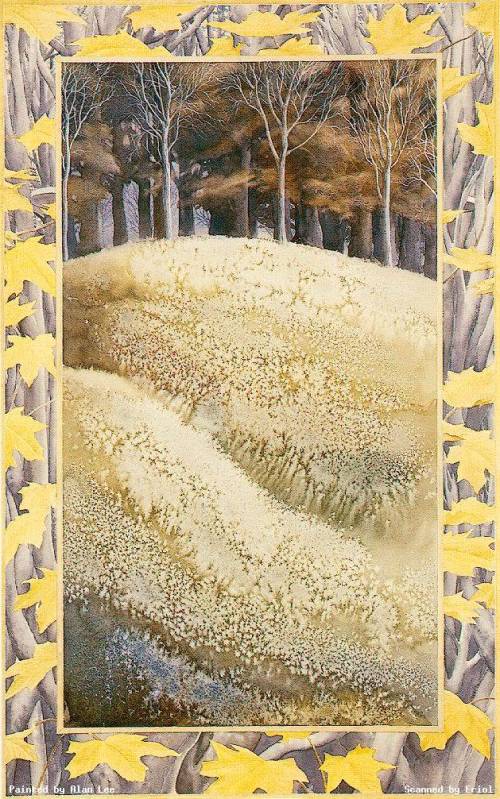

Perpetual twilight of Lothlorien. Autumn in spring at Cerin Amroth.

(Artwork from New Line Cinema, Alan Lee)

When the Fellowship reached the woodland realm of Lothlórien, we first truly experience the profound beauty, and equally profound sadness of the Elves. Legolas sings of the doomed love between Amroth and Nimrodel, and the mallorn trees–with their golden leaves that are preserved past winter, and fall at springtime–also lend a sad beauty to this realm. This sadness comes from the imminent diminishing of the race of Elves, for with all their power and beauty, their time is fleeting, and will soon pass away. These chapters seem to be Tolkien’s elegy for the Elves, who according to Galadriel are doomed either way by Frodo’s quest.

Do you not see now wherefore your coming is as to us the footstep of Doom? For if you fail, then we are laid bare to the Enemy. Yet if you succeed, then our power is diminished, and Lothlórien will fade, and the tides of Time will sweep it away. We must depart into the West, or dwindle to a rustic folk of dell and cave, slowly to forget and be forgotten.

(p. 380, FOTR) [16]

This elegiac tone–this tincture of sadness–pervades the entire novel, and the history of Middle-earth. Time grinds its wheels ever forward, rubbing-off even great heroic deeds into but faded memory of song and myth. It is the sadness inherent in memory–the sadness in the passing of things, of irrevocable distance, of recollection and forgetting.

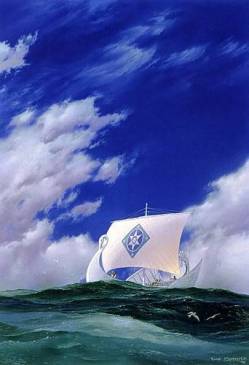

White Ships (Artwork by Ted Nasmith)

Notice this acute elegiac tone in the closing passages of The Silmarillion, describing the diminishing of the the power of the Three Rings, and the sailing into the West of the last ship from the Grey Havens, bearing their keepers, including Mithrandir (Gandalf): [17]

White was that ship and long was it a-building, and long it awaited the end of which Círdan had spoken. But when all these things were done, and the Heir of Isildur had taken up the lordship of Men, and the dominion of the West had passed to him, then it was made plain that the power of the Three Rings also was ended, and to the Firstborn the world grew old and grey. In that time the last of the Noldor set sail from the Havens and left Middle-earth forever. And the latest of all the Keepers of the Three Rings rode to the Sea, and Master Elrond took there the ship that Círdan had made ready. In the twilight of autumn it sailed out of Mithlond, until the seas of the Bent World [18] fell away beneath it, and the winds of the round sky troubled it no more, and borne upon the high airs above the mists of the world it passed into the Ancient West, and an end was to come for the Eldar of story and song.

(p. 304, The Silmarillion)

One can almost hear a deep sigh at the end. Time ennobles the past, in story and song, but also makes it subject to the fragility of memory. The reality of time is more deeply felt by the Elves who are immortal and remember those who have long been dead and forgotten. Hence, while they possess the greatest happiness, they also possess the deepest sorrow.

In contrast, Men–the Second People, the Younger Children of Ilúvatar–“were more frail, more easily slain by weapon or mischance, and less easily healed; subject to sickness and many ills; and they grew old and died.” (p. 104, The Silmarillion)

It is with this gift of freedom that the children of Men dwell only a short space in the world alive, and are not bound to it, and depart soon whither the Elves know not. Whereas the Elves remain until the end of days, and their love of the Earth and all the world is more single and more poignant therefore, and as the years lengthen ever more sorrowful. For the Elves die not till the world dies, unless they are slain or waste in grief… neither does age subdue their strength, unless one grow weary of ten thousand centuries; and dying they are gathered to the halls of Mandos, whence they may in time return. But the sons of Men die indeed, and leave the world; wherefore they are called the Guests, or the Strangers. Death is their fate, the gift of Ilúvatar…

(p. 42, The Silmarillion)

Men awoke in the land of Hildórien at the first rising of the Sun [19]. Although they were weaker, they multiplied more quickly, and were destined to eventually usurp Middle-earth. Death was the gift of Ilúvatar to Men, and where their spirits go when they die, the Elves, and even the Valars did not know, nor have the power to revoke this gift. [20] Thus, when Bëor, leader of the first Men to enter Beleriand died, the Elves witnessed for the first time the reality and mystery of death:

And when [Bëor the Old] lay dead, of no wound or grief, but stricken by age, the Eldar saw for the first time the swift waning of the life of Men, and the death of weariness which they knew not in themselves; and they grieved greatly for the loss of their friends. But Bëor at the last had relinquished his life willingly and passed in peace; and the Eldar wondered much at the strange fate of Men, for in their lore there was no account of it, and its end was hidden from them.

(p. 149, The Silmarillion)

It is a strange gift indeed, a balm from the weariness of this world, and yet disconcerting in its finality and uncertainty, and in the pain of decay that goes with it.

Kin slaying at Alqualondë (Artwork by Ted Nasmith)

For the Noldori, the return to Valinor is made even more poignant by the fact that the “curse of Cain” [21] is upon their heads. In their rebellion against the Valars, they slew their Teleri kinsmen at Alqualondë in order to highjack the ships they needed for their return to Beleriand. Thus they incurred the wrath of the Valars who cursed them thus:

Tears unnumbered shall ye shed; and the Valar will fence Valinor against you, and shut you out, so that not even the echo of your lamentation shall pass over the mountains…Ye have spilled the blood of your kindred unrighteously and have stained the land of Aman. For blood ye shall render blood, and beyond Aman ye shall dwell in Death’s shadow… And those that endure in Middle-earth and come not to Mandos [22] shall grow weary of the world as with a great burden, and shall wane, and become as shadows of regret before the younger race that cometh after. The Valar have spoken.

(p.88, The Silmarillion)

Return to Valinor (Artwork by Ted Nasmith)

Therefore, they are actually exiles in Middle-earth, and feel more and more alienated as the race of Men progress and take-over. Galadriel was one of these rebellious Noldori “who yearned to see the wide unguarded lands [of Middle-earth] and to rule there a realm at her own will” (p. 84, The Silmarillion). Their banishment includes this punishment of deterioration–to wane and become shadows of regret, to forget and be forgotten. Thus there is a strong element of (Christian) grace and forgiveness in their return to Valinor, because

[the] exile then imposed upon them as a punishment has been expiated by long years of struggle and suffering, their banishment has therefore been revoked, and their deeply implanted longing for their former lands in the Uttermost West is calling them home.

(p. 48, Master of Middle Earth)

For Galadriel, this expiation includes refusal of absolute power offered by the One Ring: “I pass the test… I will diminish, and go into the West and remain Galadriel.” Thus, though the Elves become world-weary and fade into memory and myth, there will be forgiveness awaiting them upon their return home.

Epilogue

Perhaps it is fitting to end this lecture with the longest Quenya text in LOTR, an elegy called Galadriel’s Lament, i.e. for the loss of Valinor. This poem is better known as Namárië! [23], which means “farewell”:

Ai! laurië lantar lassi súrinen,

yéni únótimë ve rámar aldaron!

Yéni ve lintë yuldar avánier

mi oromardi lissë-miruvóreva

Andúnë pella, Vardo tellumar

nu luini yassen tintilar i eleni

ómaryo airetári-lírinen.

Sí man i yulma nin enquantuva?

An sí Tintallë Varda Oiolossëo

ve fanyar máryat Elentári ortanë

ar ilyë tier undulávë lumbulë

ar sindanóriello caita mornië

i falmalinnar imbë met, ar hísië

untúpa Calaciryo míri oialë.

Sí vanwa ná, Rómello vanwa, Valimar!

Namárië! Nai hiruvalyë Valimar!

Nai elyë hiruva! Namárië!

And indeed, with that, I thank you for listening, and Namárië!

Notes:

- [9] Eru or Ilúvatar (‘all-father’) refers to God in Middle-earth. He created the Ainu, the greatest of which became the Valars who shaped Middle-earth out of the vision of Ilúvatar.

- [10] The Lord and Lady of the Golden Woods were, however, not Silvan: Galadriel was a Noldor, married to the Sindar, Celeborn.

- [11] In the film version by New Line Cinema, it was Arwen, Elrond’s daughter who commanded the river Bruinen to inundate the Nazgûl.

- [12] Glorfindel was also replaced by Arwen in the film version by New Line Cinema.

- [13] Indeed Elves are amused when the hobbits call it “magic” as when Galadriel invited Sam to also look into her Mirror: “And you?” she said to Sam. “For this is what your folk would call magic, I believe; though I do not understand clearly what they mean; and they seem to also use the same word for the deceits of the Enemy. But this, if you will, is the magic of Galadriel. Did you not say that you wished to see Elf-magic?” (p. 377, FOTR)

- [14] Tolkien’s translation: O Elbereth Starkindler from heaven gazing-afar, to thee I cry now in the shadow of (the fear of) death. O look towards me, Everwhite. [p. 278, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien] Elbereth is the Sindarin name for Varda, a Vala who kindled the Stars. There is a longer Sindarin poem from Rivendell in FOTR, p. 250.

- [15] In Cerin Amroth, Sam experienced this same intoxicating power of Elvish beauty: “It’s sunlight and bright day, right enough… I thought Elves were all for moon and stars: but this is more elvish than anything I ever heard tell of. I feel as if I was inside a song, if you take my meaning.” (p. 365. FOTR)

- [16] Compare this with what is said about the fate of Elves in The Silmarillion: “In after days, when because of the triumph of Morgoth Elves and Men became estranged, as he most wished, those of the Elven-race that lived still in Middle-earth waned and faded, and Men usurped the sunlight. Then the Quendi wandered in lonely places of the great lands and the isles, and took to the moonlight and the starlight, and to the woods and caves, becoming as shadows and memories, save those who ever and anon set sail into the West and vanished from Middle-earth.” (p.105, The Silmarillion)

- [17] Gandalf was the bearer of Narya (fire), the third of the Three Rings of the Elves. Galadriel wore Nenya (water), and the mightiest of the three, Vilya (air), was worn by Elrond. Narya had the power to strengthen hearts, which is why Gandalf is often seen rallying troops in battle to counteract the terror of Nazgûl scream.

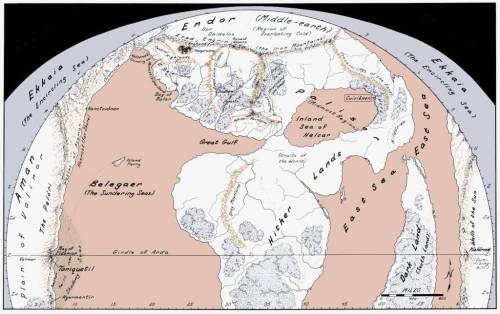

- [18] Valinor lay in central Aman, the great western continent lying between Belegaer and Ekkaia. Aman and Tol Erresëa were removed from Arda when Arda was made round at the destruction of Númenor

- [19] Hence they were called the Children of the Sun, as opposed to the Elves who awoke under the Stars.

- [20] As seen in the story of Beren and Lúthien: “These were the choices that Manwë gave to Lúthien. Because of her labours and her sorrow, she would be released from Mandos, and go to Valimar, there to dwell until the world’s end among the Valar, forgetting all griefs that her life had known. Thither Beren could not come. For it was not permitted to the Valar to withhold Death from him, which is the gift of Ilúvatar to Men. But the other choice was this: that she might return to Middle-earth, and take with her Beren, there to dwell again, but without certitude of life or joy. Then she would become mortal, and subject to a second death, even as he; and ere long she would leave the world forever, and her beauty become only a memory in song.” (p. 187, The Silmarillion)

- [21] In the Bible, Cain was banished by God for the murder of his brother Abel: “What have you done? Listen! Your brother’s blood cries from the ground. Now you are under a curse and driven from the ground, which opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you work the ground, it will no longer yield crops for you. You will be a restless wanderer on earth.” (NIV, Gen. 4:10, 11)

- [22] A Vala, the Doomsman of the Valar, keeping the Houses of the Dead. Although Elves are immortal, they may be slain or die of grief, whence their “houseless spirits shall come then to Mandos”.

- [23] Tolkien’s translation:

- Ah! like gold fall the leaves in the wind,

long years numberless as the wings of trees!

The long years have passed like swift draughts

of the sweet mead in lofty halls

beyond the West, beneath the blue vaults of Varda

wherein the stars tremble

in the voice of her song, holy and queenly.

Who now shall refill the cup for me?

For now the Kindler, Varda, the Queen of the stars,

from Mount Everwhite has uplifted her hands like clouds

and all paths are drowned deep in shadow;

and out of a grey country darkness lies

on the foaming waves between us, and mist

covers the jewels of Calacirya for ever.

Now lost, lost to those of the East is Valimar!

Farewell! Maybe thou shalt find Valimar!

Maybe even thou shalt find it! Farewell!

References:

- Ardalambion–Of the Tongues of Arda, the invented world of J.R.R. Tolkien

- Day, David, Tolkien, The Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1991, Mitchell Beazley Publishers, London.

- Fonstad, Karen Wynn, The Atlas of Middle Earth, rev. ed., 1979 Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston.

- Foster, Robert, The Complete Guide to Middle-Earth from The Hobbit to The Silmarillion, 1978, Del Rey, USA.

- Kocher, Paul H., Master of Middle-Earth, 1972, Del Rey, USA.

- Noel, Ruth S., The Languages of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, 1980, Houghton Mifflin Company, USA.

- Tolkien, J.R.R., The Fellowship of the Ring, 2nd ed., 1965, Houghton Mifflin Co., USA.

- Tolkien, J.R.R., The Return of the King, 2nd ed., 1965, Houghton Mifflin Co., USA.

- Tolkien, J.R.R., The Silmarillion, 1977, Houghton Mifflin Co., USA.

- Tolkien, J.R.R., The Tolkien Reader, 1966, Ballantine Books, NY.

- Tolkien, J.R.R., The Two Towers, 2nd ed., 1965, Houghton Mifflin Co., USA.